The release of Season 2 of Netflix’s “America’s Sweethearts: Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders” has turned what many once viewed as a glamorous sideline role into a revealing case study in elite performance, physical sacrifice, branding power, and labor reality inside the NFL.

The docuseries pulls back the curtain on one of the most recognizable cheerleading squads in the world, showing how the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders are built not just through talent and beauty, but through relentless training, emotional resilience, and an unforgiving selection process.

From the very beginning, the road to becoming a DCC starts long before anyone steps onto a football field. Hundreds of applicants submit online materials, including a headshot, full-length photo, a short introduction video, and a 60-second freestyle dance performance.

In Season 1, director Kelli Finglass notes that roughly 500 women applied online. By Season 2, the popularity of the show and the prestige of the brand had pushed that number into the thousands, turning the audition into a global competition.

The leadership at the heart of this operation is firmly rooted in the franchise’s history. Kelli Finglass and Judy Trammell, both former Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders from the 1980s, oversee the talent pipeline, while Charlotte Jones, the team’s executive vice president and chief brand officer, supervises the broader program.

From the pool of online submissions, about 75 hopefuls are invited to Frisco, Texas, for in-person solo performances. There, a panel of judges evaluates their routines, presence, and potential, voting on who will move forward in the selection process.

Even veterans are not exempt from this scrutiny. Former squad members who wish to return must audition again, performing solo routines alongside rookies. Making the team once does not guarantee a place the following year, and training camp remains a constant hurdle.

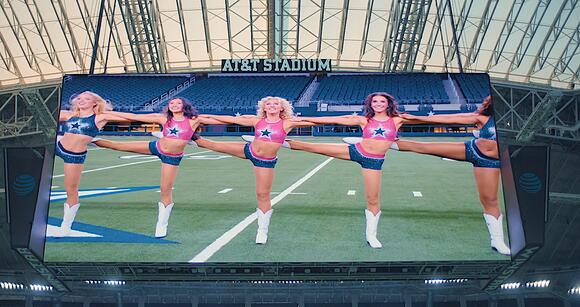

The next phase shifts from studio performances to the football environment. Candidates take their skills onto the turf, learning quickly that performing in a stadium is fundamentally different from dancing in a small room or on a competition stage.

Finglass explains in Season 2 that the organization needs “arena performers,” not just technically gifted soloists. Dancers must learn to project energy across a massive venue, reaching fans in the upper decks while maintaining sharpness, synchronization, and on-camera charisma.

Those who impress on the field advance to training camp, but the process is still far from over. Typically, around 45 candidates survive to this stage, with further cuts looming as coaches and judges fine-tune the final 36-member roster.

Former DCC Rachel Gill wrote that showmanship is a major factor in judging. Directors can help refine technique or patience with learning choreography, but performance presence is harder to teach. As she put it, you either have that intangible onstage spark, or you do not.

Training camp also marks the moment many hopefuls have dreamed about since childhood: learning the iconic “Thunderstruck” routine set to AC/DC’s anthem. For many, it is surreal to finally practice the same choreography they’ve watched for years from the stands or on television.

Kelly Villares, who auditioned in Season 1, describes learning “Thunderstruck” as both overwhelming and exhilarating. The choreography is far more complex than it appears from a distance, demanding precision, stamina, and split-second timing while maintaining the trademark DCC smile.

The “Thunderstruck” routine has been a staple since AT&T Stadium opened in 2009. Performed before every home game, it has become synonymous with the Cowboys’ game-day atmosphere and is instantly recognizable to fans across the NFL.

Within that choreography, two special positions stand out: “Point 1” and “Point 2,” located at the front of the formation. These roles are considered prestigious honors, usually reserved for veterans who embody dance excellence, leadership, and the image of the organization.

Beyond dancing, the transformation into a DCC also involves a carefully managed visual makeover. Recruits are taken to professional salons where hairstylists and makeup artists collaborate with leadership to shape looks that fit the program’s brand standards.

Finglass notes that by this stage, directors have already evaluated how candidates handle pressure in auditions. Now the focus shifts to ensuring that each woman is presented at her best, visually aligned with what has become known as the “DCC look.”

That look, however, carries immense pressure. Former cheerleader Jayln Stough reveals that there is an expectation of near-perfect presentation—flawless makeup, styled hair, manicured nails, and an always-pleasant expression that rarely allows visible sadness or vulnerability.

Stough explains that this pursuit of perfection does not stay on the field. It follows them into the locker room and everyday life, reinforcing an image standard that can be both professionally rewarding and emotionally exhausting over time.

In the end, after months of auditions, training, and evaluations, only 36 women make the final team. The squad consists of returning veterans who survived the process again and rookies who managed to impress judges at every stage.

Those who earn a place on the team receive the iconic Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders uniform, a piece of sports culture so recognizable that versions of it are displayed in the Smithsonian. Yet the uniform carries strict rules and physical expectations.

It is widely believed that cheerleaders receive only one fitted uniform, tailored to their specific measurements when they first make the squad. They are expected to maintain that size throughout their tenure, with little room for fluctuation.

Retired veteran Kat Puryear explains that you do not simply request a larger size if your body changes. If the uniform stops fitting properly, the organization questions why, adding another layer of pressure around body image and physical maintenance.

Every uniform must also be returned, even by those who retire. The garment is not a personal keepsake but a controlled symbol of the franchise, further underscoring the brand’s tight grip on image and presentation.

The docuseries also tackles mental health and body image head-on. Fourth-year veteran Victoria Kalina opens up about battling depression and disordered eating, describing how the constant requirement to fit into the same “baby uniform” can reinforce destructive patterns.

She explains that the cycle of preparing for game days, squeezing into a small uniform, and performing at a high level while struggling privately creates a relentless mental burden, especially for dancers already vulnerable to body-image pressures.

Although the team has no official height or weight requirements on paper, the series suggests that uniformity in height can be beneficial, especially given the physical demands of synchronized kick lines and partner-supported movements.

The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders’ influence stretches far beyond the sidelines. Since the 1970s, the group has been woven into American pop culture, appearing on television, in films, and at major events, making their uniform an instantly recognizable symbol of NFL entertainment.

One former cheerleader from that era recalls how powerful the title became socially. Simply telling people you were a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader could change how strangers treated you, turning you into someone everyone suddenly wanted to know.

Inside the organization, respect is formalized in language. Cheerleaders address leadership figures like Kelli Finglass and Judy Trammell as “Ma’am,” a cultural adjustment for some, particularly those from regions where such honorifics are uncommon in everyday conversation.

Abby Summers, a Season 2 contestant from Ohio, admits that saying “Yes, ma’am” felt unfamiliar at first, but she grew to understand it as a sign of respect within the structure and traditions of the organization.

Physically, the demands placed on DCC members are severe. Splits are required, high kicks are a trademark, and jumping splits are part of the team’s signature moves, all of which accumulate wear and tear on the body over time.

Puryear acknowledges long-term damage, noting that both of her hips are torn. She adds that many women experience serious back and neck issues, with some eventually requiring surgery due to the toll of years spent performing high-impact routines.

Five-year veteran Jada McLean reflects on how the job has affected her body, saying she has felt herself physically breaking down. Watching younger recruits execute “cool tricks” serves as a reminder of what she once could do more easily.

Despite the pain, many veterans admit that the moves are so integral to the identity of the DCC that they cannot imagine performing without them, even if it means pushing their bodies to the brink of injury.

At the end of a rookie’s first year, the organization commemorates her achievement with a matching pinky ring, a small but meaningful symbol that she has completed her initial season as a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader.

Public appearances introduce another set of challenges. To protect cheerleaders from inappropriate physical contact, a “no-touch” policy is enforced, often by placing a football in the hands of fans when they pose for photos with the squad.

Puryear notes that this protocol exists because some fans can become overly familiar or “handy,” particularly once they recognize individual cheerleaders by name and develop a sense of false intimacy.

Season 1 depicts a serious incident in which second-year vet Sophy Laufer reports being touched inappropriately by a photographer during a game. She alerts her teammates, who notify security and involve law enforcement at the stadium.

Although the Arlington Police Department later concluded there was insufficient evidence to classify the incident as a criminal offense, the situation reinforced the vulnerabilities cheerleaders face despite their professional environment.

McLean emphasizes that wearing the uniform does not transform them into objects. She asserts that they are human beings who worked hard for their roles and deserve respect, both in and out of uniform.

Rising visibility has also raised concerns about safety away from the stadium. Puryear recounts receiving letters at her personal address, while veteran Kelcey Wetterberg describes discovering an AirTag planted on her car after she drove home.

Wetterberg explains that, even after filing reports and cooperating with police, there is often little authorities can do until an actual physical incident occurs, leaving cheerleaders with lingering anxiety about their personal safety.

Despite the prominence of the brand, being a DCC is considered part-time, hourly employment. Busy stretches can approach the equivalent of full-time hours, but many cheerleaders still juggle two or three additional jobs to support themselves financially.

Requirements typically include around 10 home games and three to four rehearsals per week, each lasting two to three hours, from late July through the end of the Dallas Cowboys’ season, plus optional but coveted paid appearances.

McLean previously told the New York Times that she earned about 15 dollars per hour and 500 dollars per public appearance, figures that highlight how prestige does not always equate to high base pay in the world of professional cheerleading.

In Season 2, McLean, along with veterans Amanda Howard, Megan McElaney, Kleine Powell, and Armani Latimer, leads a push for better wages and improved compensation structures for current and future members.

Their efforts eventually result in what is described as a “400 percent” increase in some pay categories, though McLean later clarifies that the raise is multifaceted, with different rates applied to games, practices, and appearances.

She notes that some veterans will now earn 75 dollars per hour or more in certain scenarios, although the organization has declined to publicly confirm the exact figures, emphasizing the internal nature of the compensation model.

Latimer, who retired after Season 2, takes pride in the changes, even though she will not fully benefit from them personally. She frames the wage gains as a legacy for future generations of dancers coming into the program.

In the docuseries, Finglass acknowledges the magnitude of these changes, saying that the cheerleaders have moved mountains and fundamentally altered the organization in ways that were more than six decades overdue.

One boundary, however, remains firmly in place: there is a strict “no fraternization” policy between cheerleaders and players. Contracts explicitly forbid dating or romantic involvement with Dallas Cowboys football players.

The rule exists, in part, to protect the professional environment, avoid conflicts of interest, and maintain a clear separation between the team on the field and the entertainment squad on the sidelines.

Taken together, the revelations in “America’s Sweethearts” transform the perception of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders from a glamorous backdrop to a demanding profession, where performance, brand pressure, safety concerns, and wage battles intersect under the brightest lights in sports.