A Hall of Fame case was recently constructed for a former Atlanta Braves outfielder, but it was not the long-debated candidacy of Andruw Jones that captured attention this time.

Instead, the focus shifted to a player whose résumé has rarely sparked Cooperstown debates, yet whose name appears on the Hall of Fame ballot for what is likely his first and only appearance.

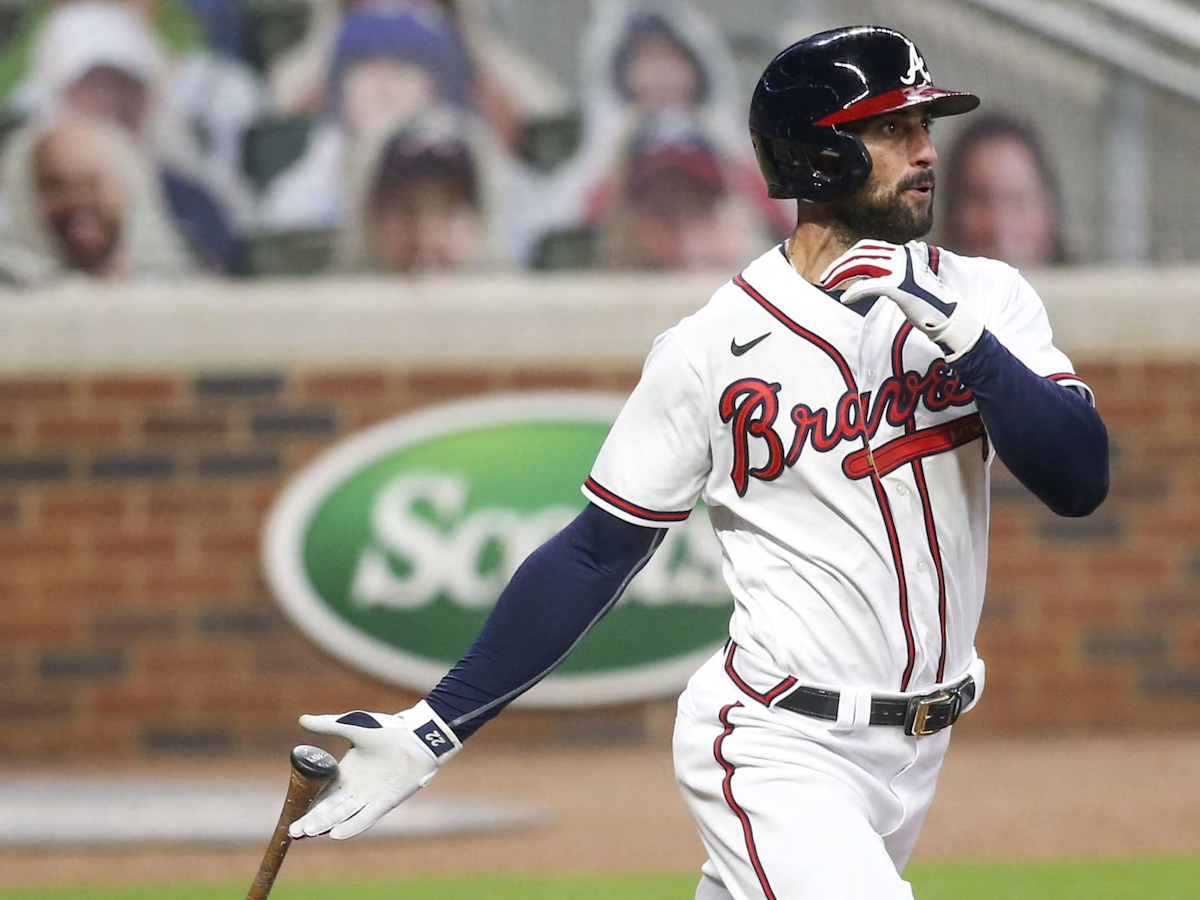

That player is Nick Markakis, a steady, durable presence whose career was defined less by dominance and more by consistency, professionalism, and quiet excellence.

Sports Illustrated columnist Tom Verducci took on the exercise of building a Hall of Fame case for every first-time candidate on this year’s ballot.

By nature, that assignment requires creativity, perspective, and a willingness to examine careers that exist on the fringes of traditional Hall of Fame standards.

Markakis was among those first-timers, and while few believe his candidacy will gain traction, Verducci approached the task with both seriousness and a sense of humor.

The reality is that most first-time candidates do not gain immediate entry into Cooperstown, and many fall off the ballot entirely after one year.

Markakis almost certainly falls into that category, not due to a lack of quality, but because Hall of Fame voting historically favors transcendent greatness over sustained reliability.

Understanding that reality, Verducci leaned into the lighter side of the exercise while still respecting the substance of Markakis’ career.

One of the more humorous observations noted that Markakis owns the highest career WAR, at 33.7, among all players who attended Young Harris College.

Young Harris College, of course, is more widely known to movie audiences as a filming location for Trouble with the Curve, starring Clint Eastwood.

The note was clearly tongue-in-cheek, an intentional reminder that not every Hall of Fame argument must be solemn or overly rigid.

In an era defined by constant urgency and heavy debates, the ability to enjoy baseball history with a smile still matters.

Yet beneath the humor, Verducci did not dismiss Markakis’ actual accomplishments, instead highlighting the traits that defined his long career.

“Markakis did not have much power for a corner outfielder,” Verducci wrote, “but he was a splendid defender with a line-drive stroke who never wanted a day off.”

That description captures the essence of Markakis better than any single statistic could.

He was not a slugger in the modern sense, nor a highlight-reel star, but he was relentlessly dependable.

Durability became one of Markakis’ defining attributes, particularly during the peak of his career.

Verducci highlighted that Markakis played at least 160 games in a season seven different times.

In the wild card era, only Ichiro Suzuki logged more such seasons, with eight.

That level of availability is increasingly rare in modern baseball, where injuries and rest management dominate roster planning.

Markakis’ willingness to take the field every day became a competitive advantage, even if it rarely generated headlines.

Over the course of his career, Markakis accumulated 2,388 hits, a total that reflects longevity, consistency, and sustained competence.

He was not the type of hitter who overwhelmed pitchers, but he rarely gave away at-bats.

His approach relied on contact, discipline, and an understanding of situational hitting that managers value deeply.

Markakis’ lone All-Star appearance came late in his career, at age 34, during his tenure with the Braves.

That selection served as a recognition of both his performance and his reputation within the league.

It was not a coronation, but rather an acknowledgment of a player who had quietly earned respect over time.

While Verducci did not explicitly emphasize it, Markakis’ defensive résumé deserves additional context.

He was a three-time Gold Glove Award winner, a distinction that reflects sustained excellence rather than isolated moments.

At one point, Markakis held the Major League record for consecutive games without committing an error in the outfield.

That streak reached 398 straight games, a testament to precision, focus, and routine execution.

The record has since been surpassed by Robbie Grossman, who extended the mark to 440 games.

Even so, Markakis’ streak remains one of the most remarkable demonstrations of defensive consistency in recent baseball history.

Defense is often undervalued in Hall of Fame discussions, particularly when it lacks dramatic flair.

Markakis’ excellence was quiet, efficient, and almost invisible when done correctly.

That invisibility is part of why his candidacy struggles to resonate with traditional Hall of Fame metrics.

There is no illusion here, and even his most ardent supporters understand the outcome.

Nick Markakis is not a Hall of Famer in the conventional sense.

He lacks the counting stats, peak dominance, and historical imprint that typically define Cooperstown induction.

If there is a former Braves outfielder with a legitimate Hall of Fame path, it remains Andruw Jones.

Jones’ defensive brilliance, sustained power, and advanced metrics have steadily pushed him closer to election.

Each year, his vote totals have climbed, placing him within striking distance of eventual induction.

Jones represents the archetype of a player whose greatness was once underappreciated and later reevaluated through deeper analysis.

Markakis, by contrast, occupies a different space in baseball history.

His career invites reflection rather than debate.

There is value in examining players who were never stars, yet were essential to their teams’ daily function.

Baseball history is not built solely by legends, but by professionals who filled lineups year after year.

Markakis embodied that role as well as anyone in his generation.

Perhaps the most fitting recognition for Markakis lies not in Cooperstown, but in a conceptual space sometimes referred to as the “Hall of Pretty Good.”

That unofficial designation celebrates players whose careers were admirable, reliable, and worthy of remembrance, even if they fall short of immortality.

Another former Brave has already found his way into that category.

Andrelton Simmons was acknowledged in that context back in October, recognized for defensive brilliance that transcended offensive limitations.

Being an All-Star or winning Gold Gloves does not disqualify a player from falling short of the Hall of Fame.

Nor should it diminish the appreciation of what they contributed.

Markakis was a good ballplayer, by any honest measure.

He played hard, played often, and played the game the right way.

In a sport increasingly defined by extremes, there is still room to honor consistency.

His Hall of Fame case may not succeed, but it does not need to.

Sometimes, the conversation itself is the reward.

And in remembering players like Nick Markakis, baseball honors not just greatness, but the enduring value of reliability.